(Courtesy of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia)

(Courtesy of Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia)

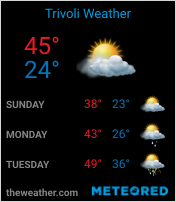

At right is a photo of the champions of the 2002 World Radiosport Team Championship (WRTC), Helsinki, Finland.

At right is a photo of the champions of the 2002 World Radiosport Team Championship (WRTC), Helsinki, Finland.

Contesting (also known as radiosport) is a competitive activity pursued by amateur radio operators. In a contest, an amateur radio station, which may be operated by an individual or a team, seeks to contact as many other amateur radio stations as possible in a given period of time and exchange information. Rules for each competition define the amateur radio bands, the mode of communication that may be used, and the kind of information that must be exchanged. The contacts made during the contest contribute to a score by which stations are ranked. Contest sponsors publish the results in magazines and on web sites.

Contesting grew out of other amateur radio activities in the 1920s and 1930s. As transoceanic communications with amateur radio became more common, competitions were formed to challenge stations to make as many contacts as possible with amateur radio stations in other countries. Contests were also formed to provide opportunities for amateur radio operators to practice their message handling skills, used for routine or emergency communications across long distances. Over time, the number and variety of radio contests has increased, and many amateur radio operators today pursue the sport as their primary amateur radio activity.

There is no international authority or governance organization for this sport. Each competition is sponsored separately and has its own set of rules. Contest rules do not necessarily require entrants to comply with voluntary international band plans. Participants must, however, adhere to the amateur radio regulations of the country in which they are located. Because radio contests take place using amateur radio, competitors are generally forbidden by their national amateur radio regulations from being compensated financially for their activity. High levels of amateur radio contest activity, and contesters failing to comply with international band plans, can result in friction between contest participants and other amateur radio users of the same radio spectrum.

Contesting basics

Radio contests are principally sponsored by amateur radio societies, radio clubs, or radio enthusiast magazines. These organizations publish the rules for the event, collect the operational logs from all stations that operate in the event, cross-check the logs to generate a score for each station, and then publish the results in a magazine, in a society journal, or on a web site. Because the competitions are between stations licensed in the Amateur Radio Service (with the exception of certain contests which sponsor awards for shortwave listeners), which prohibits the use of radio frequencies for pecuniary interests, there are no professional radio contests or professional contesters, and any awards granted by the contest sponsors are typically limited to paper certificates, plaques, or trophies.[1]

At left is a photo of a multioperator contest effort involving a team of operators at one station.

At left is a photo of a multioperator contest effort involving a team of operators at one station.

During a radio contest, each station attempts to establish two-way contact with other licensed amateur radio stations and exchange information specific to that contest. The information exchanged could include a signal report, a name, the U.S. state or Canadian province in which the station is located, the geographic zone[2] in which the station is located, the Maidenhead grid locator in which the station is located, the age of the operator, or an incrementing serial number. For each contact, the radio operator must correctly receive the call sign of the other station, as well as the information in the "exchange", and record this data, along with the time of the contact and the band or frequency that was used to make the contact, in a log.

A contest score is computed based on a formula defined for that contest. A typical formula assigns some number of points for each contact, and a "multiplier" based on some aspect of the exchanged information. The rules for most contests held on the VHF amateur radio bands in North America assign a new multiplier for each new Maidenhead grid locator in the log, rewarding the competitors that make contacts with other stations in the most locations. Many HF contests reward stations with a new multiplier for contacts with stations in each country - often based on the "entities" listed on the DXCC country list maintained by the American Radio Relay League ("ARRL"). Depending on the rules for a particular contest, each multiplier may count once on each radio band or only once during the contest, regardless of the radio band on which the multiplier was first earned. The points earned for each contact can be a fixed amount per contact, or can vary based on a geographical relationship such as whether or not the communications crossed a continental or political boundary. Some contests, such as the Stew Perry Top Band Distance Challenge, award points that are scaled to the distance separating the two stations.[3] Most contests held in Europe on the VHF and microwave bands award 1 point per kilometre of distance between the stations making each contact.[4]

After they are received by the contest sponsor, logs are checked for accuracy. Points can be deducted or credit or multipliers lost if there are errors in the log data for a given contact. Depending on the scoring formula used, the resulting scores of any particular contest can be either a small number of points or in the millions of points. Most contests offer multiple entry categories, and declare winners in each category. Some contests also declare regional winners for specific geographic subdivisions, such as continents, countries, U.S. states, or Canadian provinces.[5]

The most common entry category is the single operator category and variations thereof, in which only one individual operates a radio station for the entire duration of the contest. Subdivisions of the single operator category are often made based on the highest power output levels used during the contest, such as a QRP category for single operator stations using no more than five watts output power, or a High Power category that allows stations to transmit with as much output power as their license permits. Multi-operator categories allow for teams of individuals to operate from a single station, and may either allow for a single radio transmitter or several to be in use simultaneously on different amateur radio bands. Many contests also offer team or club competitions in which the scores of multiple radio stations are combined and ranked.[6]

Types of contests

A wide variety of amateur radio contests are sponsored every year. Contest sponsors have crafted competitive events that serve to promote a variety of interests and appeal to diverse audiences. Radio contests typically take place on weekends or local weeknight evenings, and can last from a few hours to forty-eight hours in duration. The rules of each contest will specify which stations are eligible for participation, the radio frequency bands on which they may operate, the communications modes they may employ, and the specific time period during which they may make contacts for the contest.

A wide variety of amateur radio contests are sponsored every year. Contest sponsors have crafted competitive events that serve to promote a variety of interests and appeal to diverse audiences. Radio contests typically take place on weekends or local weeknight evenings, and can last from a few hours to forty-eight hours in duration. The rules of each contest will specify which stations are eligible for participation, the radio frequency bands on which they may operate, the communications modes they may employ, and the specific time period during which they may make contacts for the contest.

The rules of a contest will indicate which stations are eligible to participate in the competition, and which other amateur radio stations they may contact. Some contests restrict participation to stations in a particular geographic area, such as a continent or country. Contests like the European HF Championship[7] aim to foster competition between stations located in one particular part of the world, specifically Europe. There are contests in which any amateur radio station worldwide may participate and make contact with any other stations for contest credit. The CQ World Wide DX Contest permits stations to contact other stations anywhere else on the planet, and attracts tens of thousands of participating stations each year.[8] In large contests the number of people taking part is a significant percentage of radio amateurs active on the HF bands, although they in themselves are a small percentage of the total amateurs in the world.

There are regional contests that invite all stations around the world to participate, but restrict which stations each competitor may contact. For example, Japanese stations in the Japan International DX Contest (sponsored by Five Nine magazine) may only contact other stations located outside of Japan and vice versa.[9] There are also contests that limit participation to just the stations located in a particular continent or country, even though those stations may work any other station for points.

All contests use one or more amateur radio bands on which competing stations may make two-way contacts. HF contests use one or more of the 160 meter, 80 Meter, 40 Meter, 20 Meter, 15 Meter, and 10 Meter bands. VHF contests use all the amateur radio bands above 50 MHz. Some contests permit activity on all HF or all VHF bands, and may offer points for contacts and multipliers on each band. Other contests may permit activity on all bands but restrict stations to making only one contact with each other station, regardless of band, or may limit multipliers to once per contest instead of once per band. Most VHF contests in North America are similar to the ARRL June VHF QSO Party,[10] and allow contacts on all the amateur radio bands 50 MHz or higher in frequency. Most VHF contests in the United Kingdom, however, are restricted to one amateur radio band at a time.[11] An HF contest with world wide participation that restricts all contest activity to just one band is the ARRL 10 Meter Contest.[12]

Contests exist for enthusiasts of all modes. Some contests are restricted to just CW emissions using the Morse code for communications, some are restricted to telephony modes and spoken communications, and some employ digital emissions modes such as RTTY or PSK31. Many popular contests are offered on two separate weekends, one for CW and one for telephony, with all the same rules. The CQ World Wide WPX Contest, for example, is held as a phone-only competition one weekend in March, and a CW-only competition one weekend in May.[13] Some contests, especially those restricted to a single radio frequency band, allow the competing stations to use several different emissions modes. VHF contests typically permit any mode of emission, including some specialty digital modes designed specifically for use on those bands. As with the other variations in contest rules and participation structure, some contest stations and operators choose to specialize in contests on certain modes and may not participate seriously in contests on other modes. Large, worldwide contests on the HF bands can be scheduled for up to forty-eight hours in duration. Typically, these large worldwide contests run from 0000 UTC on Saturday morning until the end of 2359 UTC Sunday evening. Regional and smaller contests often are scheduled for a shorter duration, with twenty-four hours, twelve hours, and four hours being common variations.

Many contests employ a concept of "off time" in which a station may operate only a portion of the available time. For example, the ARRL November Sweepstakes is thirty hours long, but each station may be on the air for no more than twenty-four out of the thirty hours.[14] The off-time requirement forces competitive stations to decide when to be on the air making contacts and when to be off the air, and adds a significant element of strategy to the competition. Although common in the 1930s, only a small number of contests today take place over multiple weekends. These competitions are called "cumulative" contests, and are generally limited to the microwave frequency bands. Short "sprint" contests lasting only a few hours have been popular among contesters that prefer a fast-paced environment, or who cannot devote an entire weekend to a radio contest. A unique feature of the North American Sprint contest is that the operator is required to change frequency after every other contact, introducing another operational skills challenge.[15] Whatever the length of the contest, the top operators are frequently those that can best maintain focus on the tasks of contest operating throughout the event.

The wide variety of contests attracts a large variety of contesters and contest stations. The rules and structure of a particular contest can determine the strategies used by competitors to maximize the number of contacts made and multipliers earned. Some stations and operators specialize in certain contests, and either rarely operate in others, or compete in them with less seriousness. As with other sports, contest rules evolve over time, and rule changes are one of the primary sources of controversy in the sport.

History of contesting

The origin of contesting can be traced to the Trans-Atlantic Tests of the early 1920s, when amateur radio operators first attempted to establish long distance radiocommunications across the Atlantic Ocean on the short wave amateur radio frequencies. Even after the first two-way communications between North America and Europe were established in 1923,[16] these tests continued to be annual events at which more and more stations were successful in establishing two-way contacts over greater and greater distances. In 1927, the American Radio Relay League, which had been principal in organizing and publicizing these tests, proposed a new format for the annual event, encouraging stations to make as many two-way contacts with stations in other countries as possible. The 1928 International Relay Party, as the event was renamed, was the first organized amateur radio contest.[17] The International Relay Party was an immediate success, and was sponsored annually by the ARRL from 1927 through 1935.[18] In 1936, the contest name changed to the ARRL International DX Contest, the name under which it is known today.

To complement the burst of activity and interest being generated in DX communications by the popularity of the International Relay Parties, the ARRL adopted a competitive operating format for events designed for non-international contacts. The first ARRL All-Sections Sweepstakes Contest was started in 1930.[19] The Sweepstakes required a more complicated exchange of information for each two-way contact that was adapted from the message header structure used by the National Traffic System. The competition was immediately popular, both with those operators active in the NTS who participated as an opportunity to gauge the merits of their station and operating skills, and among those for whom the competitive excitement of the event was the primary attraction. The contest, sponsored annually by the ARRL, became known as the ARRL November Sweepstakes in 1962.[20]

Another important innovation in early contesting was the development of Field Day operating events. The earliest known organized field day activity was held in Great Britain in 1930, and was soon emulated by small events through Europe and North America.[21] The first ARRL International Field Day was held in July, 1933, and publicized through the ARRL's membership journal QST. [22] Field day events were promoted as an opportunity for radio amateurs to operate from portable locations, in environments that simulate what might be encountered during emergency or disaster relief situations. Field day events have traditionally carried the same general operating and scoring structures as other contests, but the emphasis on emergency readiness and capability has historically outweighed the competitive nature of these events.

Modern contests draw upon the heritage of DX communications, traffic handling, and communications readiness. Since 1928, the number and variety of competitive amateur radio operating events have increased. In 1934, contests were sponsored by radio societies in Australia, Canada, Poland, and Spain, and the ARRL sponsored a new contest specifically for the ten meter amateur radio band. By the end of 1937, contests were also being sponsored in Brazil, France, Germany, Great Britain, Hungary, Ireland, and New Zealand. The first VHF contest was the ARRL VHF Sweepstakes held in 1948,[23] and the first RTTY contest was sponsored by the RTTY Society of Southern California in 1957.[24] The first publication dedicated exclusively to the sport, the National Contest Journal, began circulation in the United States in 1973.[25] Recognizing the vitality and maturity of the sport, CQ Amateur Radio magazine established the Contest Hall of Fame in 1986.[26] By the turn of the century, contesting had become an established world wide sport, with tens of thousands of active competitors, connected not just through their on air activities, but with specialist web sites, journals, and conventions.

Without a single world wide organizing body or authority for the sport, there has never been a world ranking system by which contesters could compare themselves. The vast differences contesters face in the locations from which they operate contests, and the effect that location has on both radio propagation and the proximity to major populations of amateur radio operators also conspired to make comparisons of the top performers in the sport difficult. The first World Radiosport Team Championship event was held in July, 1990 in Seattle, Washington, USA, and was an effort to overcome some of these issues by inviting the top contesters from around the world to operate a single contest from similar stations in one compact geographic area. Twenty-two teams of two operators each represented fifteen countries, and included some top competitors from the Soviet Union and nations of the former Eastern Bloc for whom the trip was their first to a western nation. Subsequent WRTC events have been held in 1996 (San Francisco, California, USA), 2000 (Bled, Slovenia), 2002 (Helsinki, Finland), and 2006 (Florianópolis, Brazil). The closest thing to a world championship in the sport of contesting, WRTC 2010 will take place in Moscow, Russia.[27]

Contesting activity

The scale of activity varies from contest to contest. The largest contests are the annual DX contests that allow world wide participation. Many of these DX contests have been held annually for fifty years or more, and have devoted followings. Newer contests, those that intentionally restrict participation based on geography, and those that are shorter in duration tend to have fewer participating stations and attract more specialized operators and teams. Over time, contests that fail to attract enough entrants will be abandoned by their sponsor, and new contests will be proposed and sponsored to meet the evolving interests of amateur radio operators.

In a specialised contest in the microwave frequency bands, where only a handful of radio amateurs have the technical skills to construct the necessary equipment, a few contacts just a few kilometers away may be enough to win. In the most popular VHF contests, a well-equipped station in a densely populated region like Central Europe can make over 1,000 contacts on two meters in twenty-four hours. In the CQ World Wide DX Contest, the world's largest HF contest, leading multi-operator stations on phone and CW can make up to 25,000 contacts in a forty-eight hour period, while even single operators with world-class stations in rare locations have been known to exceed 10,000 contacts, an average of over three per minute, every minute. Over 30,000 amateur radio operators participated in the phone weekend of the 2000 CQ World Wide DX Contest, and the top-scoring single operator station that year, located in the Galápagos Islands, made over 9,000 contacts.[28] Other HF contests are not as large, and some specialty events, such as those for QRP enthusiasts, can attract no more than a few dozen competitors.

Station locations

The geographic location of a station can impact its potential performance in radio contests. In almost all contests it helps to be in a rare location close to a major population center. Because the scoring formula in most contests uses the number of different locations contacted (such as countries, states or grid locators) as a multiplier, contacts with stations in rare locations are in high demand. In contests on the VHF and higher frequency bands, having a location at a high altitude with unobstructed line of sight in all directions is also a major advantage. With range limited to around 1000 kilometers in normal radio propagation conditions, a location on high ground close to a major metropolitan area is an often unbeatable advantage in VHF contests. In the large international HF DX contests, stations in the Caribbean Sea and the North Atlantic Ocean, close to Europe and eastern North America with their high densities of active contest stations, are frequently the winners. Aruba, Curaçao, the Canary Islands, the Cape Verde Islands, Madeira Island, coastal Morocco and the islands of Trinidad and Tobago have been the sites of some of the most famous radio contesting victories in the large world wide contests. Competition between stations in large countries, such as Canada, Russia, or the United States can be greatly affected by the geographic locations of each station. Because of these variations, some stations may specialize in only those contests where they are not at a disadvantage, or may measure their own success against only nearby rivals.

Many radio amateurs are happy to contest from home, often with relatively low output power and simple antennas. Some of these operators at modest home stations operate competitively and others are simply on the air to give away some points to serious stations or to chase some unusual propagation. More serious radio contesters will spend significant sums of money and invest a lot of time building a potentially winning station, whether at home, a local mountain top, or in a distant country. Operators without the financial resources to build their own station establish relationships with those that do and "guest operate" at other stations during contests. Contesting is often combined with a DX-pedition, where amateur radio operators travel to a location where amateur radio activity is infrequent or uncommon.

Several contests are designed to encourage outdoor operations, and are known as field days. The motivating purpose of these events is to prepare operators for emergency readiness, but many enjoy the fun of operating in the most basic of circumstances. The rules for most field day events require or strongly incent participating stations to use generator or battery power, and temporary antennas.[29] This can create a more level playing field, as all stations are constructed in a similar manner.

Typical contest exchange

Contacts between stations in a contest are often brief. A typical exchange between two stations on voice — in this case between a station in England and one in New Zealand in the CQ World Wide DX Contest — might proceed as follows:

Station 1: CQ contest Mike Two Whiskey, Mike Two Whiskey, contest.

(Station M2W is soliciting a contact in the contest)

Station 2: Zulu Lima Six Quebec Hotel

(The station calling, ZL6QH, gives only his callsign. No more information is needed.)

Station 1: ZL6QH 59 14 (said as "five nine one four").

(M2W confirms the ZL6QH call sign, sends a signal report of 59, and is in Zone 14 (Western Europe).)

Station 2: Thanks 59 32 (said as "five nine three two").

(ZL6QH confirms reception of M2W's exchange, sends a signal report of 59, and is in Zone 32 (South Pacific).)

Station 1: Thanks Mike Two Whiskey

(M2W confirms ZL6QH's exchange, is now listening for new stations.)

On Morse code, suitable well-known abbreviations are used to keep the contact as brief as possible. Skilled contesters can maintain a "rate" over four contacts per minute on Morse code, or up to ten contacts per minute on voice during peak propagation periods, using this short format.[30] The peak rate of contacts that can be made during contests that employ longer exchanges with more information that must be sent, received, and acknowledged, will be necessarily lower.

Logs and log checking

Most serious competitive stations log their contest contacts using contest logging software, although some continue to use paper and pencil. There are many different software logging programs written specifically for radio contesting. Computer logging programs can handle many additional duties besides simply recording the log data; they can keep a running score based upon the formula of the contest, track which available multipliers have been "worked" and which have not, and provide the operator with visual clues about how many contacts are being made on which bands. Some contest software even provide a means to control the station equipment via computer, retrieve data from the radio and send pre-recorded morse code, voice or digital messages. After the conclusion of a contest, each station must submit its operational log to the contest sponsor. Many sponsors accept logs by e-mail, by upload on web sites, or even by postal mail.

Once a contest sponsor receives all the logs from the competitors, the logs undergo a process known as "cross-checking." In cross-checking, the contest sponsor will match up the contacts recorded in the logs and look for errors or omissions. Most contests enforce stiff points penalties for inaccuracies in the log, which means that the need for speed in operation must be balanced against the requirement for accuracy. It is not uncommon for a station to lead in points at the end of the contest, but slip behind a more accurate competitor after the cross-checking process has assessed penalties. Some contest sponsors provide custom log checking reports to participating stations that offer details about the errors in their log and how they were penalized.[31]

Results and awards

Most contests are sponsored by organizations that either publish a membership journal, or sell a radio enthusiast magazine as their business. The results of radio contest events are printed in these publications, and often include an article describing the event and highlighting the victors. Contest results articles might also include photographs of radio stations and operators in the contest, and a detailed listing of the scores of every participating station. In addition to publication in magazines and journals, many contest sponsors also publish results on web sites, often in a format similar to that found in print. Some contest sponsors offer the raw score results data in a format that enables searching or other data analysis. The American Radio Relay League, for example, offers this raw line score data to any of its members, and offers the summary report of the winners and the line score data in a non-searchable format to anyone through their web site.[32]

Because radio contests take place using amateur radio, competitors are forbidden by regulation from being compensated financially for their activity. This international regulatory restriction of the Amateur Radio Service precludes the development of a professional sport. In addition to the recognition of their peers, winners in radio contests do, however, often receive paper certificates, wooden plaques, trophies, engraved gavels, or medals in recognition of their achievements. Some contests provide trophies of nominal economic value that highlight their local agricultural or cultural heritage, such as smoked salmon (for the Washington State Salmon Run contest) or a bottle of wine (for the California QSO Party).

See also

Look up contesting in Wiktionary, the free dictionary.

- The Contesting Compendium - a collection of information about contesting

- Contest logging software - Contest logging software

- Open Contesting Wiki - Contesting Information

- Contesting.com - Contesting forums, news and information

- Contest Blogs Blogging about Contesting

- Contesting controversies

- Contesting technology

References

Cited References

- International Telecommunications Union (2005). Radio Regulations: Article 1, Section III, paragraph 1.59. Retrieved Jan. 20, 2006

- CQ Amateur Radio. CQ DX Zones of the World map. Originally published 1947. Retrieved Jan. 20, 2006

- Boring Amateur Radio Club (2006). Rules, 11th Stew Perry Top Band Distance Challenge. Retrieved Jan. 24, 2006.

- Radio Society of Great Britain General Rules for VHF Contests (2006), [1], Deutscher Amateur Radio Club General Rules for VHF Contests (2006) [2].

- An example of published results that break down winning entries by continent: Japan Amateur Radio League (2004). Results of the 45th All Asian DX Contest. Retrieved Jan. 20, 2006.

- American Radio Relay League (2005). Club Competition. Retrieved Jan. 20, 2006.

- Slovenia Contest Club (2005). Rules, European HF Championship. Retrieved Jan. 20, 2006.

- CQ Amateur Radio (2005). CQ World Wide DX Contest. Retrieved Jan. 20, 2006.

- JIDX Contest Committee (2005). Japan International DX Contest Rules. Retrieved Jan. 20, 2006.

- American Radio Relay League (2005). 2005 ARRL June VHF QSO Party Rules. Retrieved Jan. 23, 2006.

- Radio Society of Great Britain VHF Contest Committee (2006). RSGB VHF/UHF/SHF Contests Calendar 2006. Retrieved Jan. 23, 2006.

- Jones, David K4DLJ (2005). "The 2004 ARRL 10 Meter Contest Results". QST. July, 2005, p. 101.

- Bolia, Stephen N8BJQ (2006). CQ WPX Contest. Retrieved Jan. 23, 2006.

- American Radio Relay League (2005). 2005 ARRL November Sweepstakes Rules. Retrieved Jan. 20, 2006.

- National Contest Journal (2005). NAQP CW/SSB/RTTY Rules. Retrieved Jan. 24, 2006.

- Warner, K.B. 1BHW (1923). "The Transatlantic Triumph". QST. Feb., 1923, p. 7.

- Handy, F.E. 1BDI (1927). "Coming--An International Relay Party". QST. Mar., 1927, p. 28.

- Handy, F.E. W1BDI (1935). "The Seventh International Relay Competition". QST. Feb. 1935, p. 34.

- Battey, E.L. W1UE (1930). "The All-Section Sweepstakes Contest". QST. May, 1930, p. 43.

- Handy, F.E. W1BDI (1962). "The November Sweepstakes". QST. Nov., 1962, p. 81.

- Warner, Kenneth W1EH (1930). "British Societies...Club Field Day". QST. June, 1930. p. 7.

- Handy, F.E. W1BDI (1933). "First Annual Field Day Report". QST. Sep., 1933, p. 35.

- Tilton, E.P. W1HDQ (1947). "VHF Sweepstakes, January 17th-18th". QST. Dec., 1947, p. 128.

- "RTTY Sweepstakes Announcement". QST (Operating News). Oct. 1957, p. 101.

- American Radio Relay League (1999). NCJ Collection CD-ROM 1973-1998. CD-ROM. ISBN 0-87259-773-3.

- CQ Amateur Radio (2003). Members, CQ Contest Hall Of Fame (as of May 2003). Retrieved Jan. 20, 2006.

- World Radiosport Team Championship official web site.

- Cox, Bob K3EST (2001). "Results of the 2000 CQ WW DX SSB Contest". CQ Amateur Radio. Aug., 2001, p. 11.

- American Radio Relay League (2005). Field Day 2005 Rules. Retrieved Jan. 24, 2006.

- Klimoff, Timo OH1NOA. Rate is King. Retrieved April 2, 2007.

- CQ World Wide Contest Committee (2003). Guide to CQWW DX-Contest UBN and NIL Reports. Retrieved Jan. 24, 2006.

- American Radio Relay League (2006). ARRL Contest Results. Retrieved Jan. 24, 2006.

General References

- DeSoto, Clinton (1936). 200 Meters and Down. West Hartford, Connecticut, USA: American Radio Relay League.

- Ford, Steve WB8IMY (1996). The ARRL Operating Manual. "Chapter 7: Contests". West Hartford, Connecticut, USA: American Radio Relay League. Fifth Edition.

- Lombry, Thierry ON4SKY (2005). "The History of Amateur Radio". Retrieved Dec. 8, 2005.